At the same time, Donald Triplett was gifted with unique skills that baffled those around him. Don notably had an exceptional memory, more than capable of reciting psalms and catechisms at the very young age of two. Don was proficient in rapid mental multiplication, capable of answering "87 times 23" quickly and with no hesitation according to Franz Polgar, one of his psychologists. He had perfect pitch and was able to identify any musical note on the piano as they were played.

Even with his phenomenal abilities at such a young age, his gifts could not save him from being institutionalized at three years old as per his doctor's orders. This was common practice for any person who strayed far from "normal" during that era. At the time, the remedy advised to parents was to simply forget the child and move on with their lives. But the Tripletts did not forget about Don. They continued to visit him every month and eventually brought him back home to Mississippi. It was during this time that they started visiting Leo Kanner, a psychiatrist in Baltimore. At first, Kanner was puzzled. Don did not fit into any of the descriptions for any of the disorders known at that time. In an attempt to better understand Don and give him a diagnosis, Kanner requested for more visits with the "peculiar" child. After these visits with Don and encounters of ten other cases of children with similar behavior, Kanner ultimately published a groundbreaking paper detailing the terms of his new disorder, autism, in which Donald Triplett was referred to as "Case 1." Donald Triplett was now considered "autism's first child."

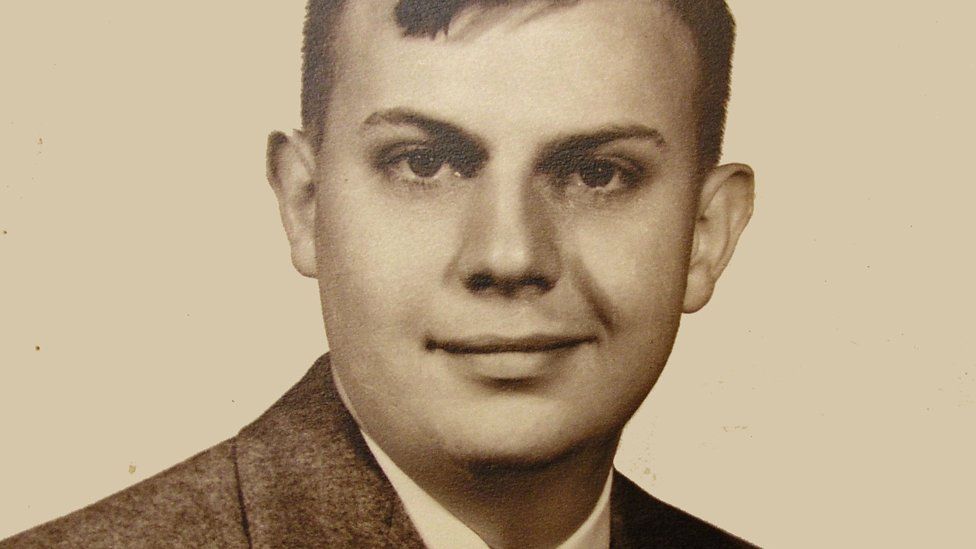

Images provided by: Triplett Family Archive & ABC News

However, Don and the Tripletts chose to distance themselves from the limelight. Don would end up living a modest and gleeful life, contrary to the mold that was set for him as an autistic child. Don was enrolled in his local high school, where he was lovingly accepted by his classmates and teachers. He would then graduate from Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi, with a bachelor's degree in French. In the same college, his friends frequently aided him and, though in vain, attempted to train Don to live more independently.

After graduation, Don returned to his hometown and happily lived in his childhood home, playing golf with his friends daily and working in his family's bank for the next 65 years of his life. He was well-known and beloved by his community, who vowed to protect and care for him. Autism's first child also happened to be one of the first to conquer it.

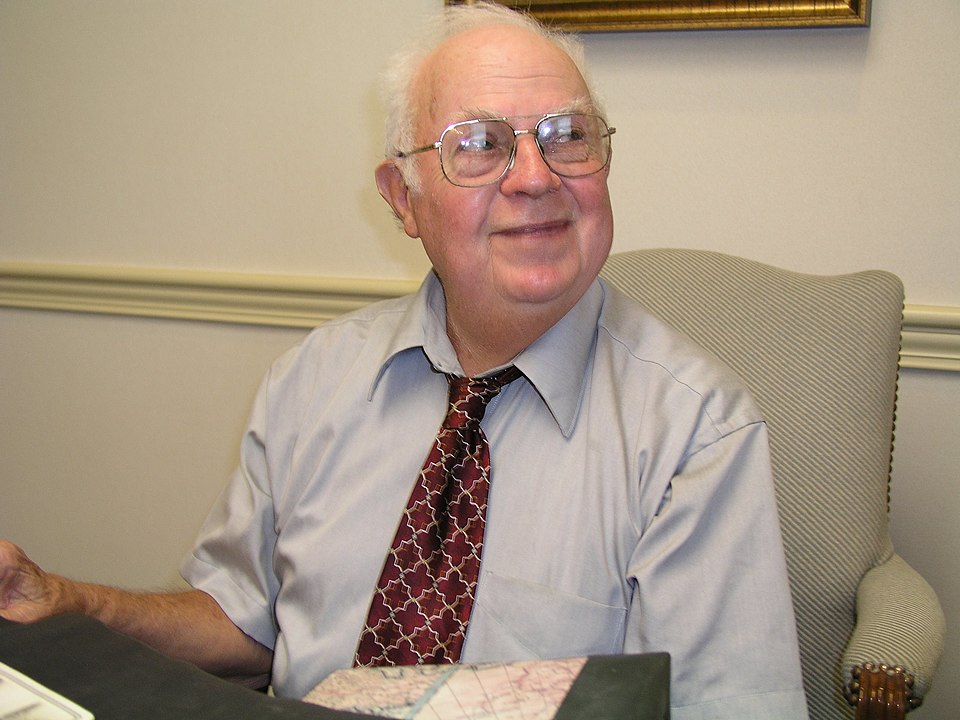

Of course, Don's autism did not go away. Late into his senior years, he still had his strange obsession with numbers and his sporadic and rapid speech. Instead, due largely to his community, friends, and family, he was able to overcome the difficulties that he was bound to face. They were there with Don every step of the way, letting him live as he pleased yet supported him and integrated him into their society. Because of this, Don, in his adulthood, did not have to face many of the isolation problems he experienced as a child—problems many autistic people continue to bear today. This does not mean Don had life easy, because he, too, faced his fair share of problems in life. But it does mean that we all have the power and impact to help people like Don together. It takes a village to raise an autistic child. Will you be a part of it?

Images provided by: Yuval Levental & PBS

created with

Website Builder Software .